Online security can take many forms, whether it’s a company’s privacy policy or the password you choose for your email.

This chapter discusses Americans’ views of and habits toward privacy policies, passwords and cybersecurity. In some cases, these opinions and experiences differ significantly by age, education level, race and ethnicity.

If you’re online, you’ve likely had a company disclose its privacy policy. That document explains how they collect, use or generally manage user data.

The survey reveals three key insights about privacy policies that people may come across online or on their smartphone.

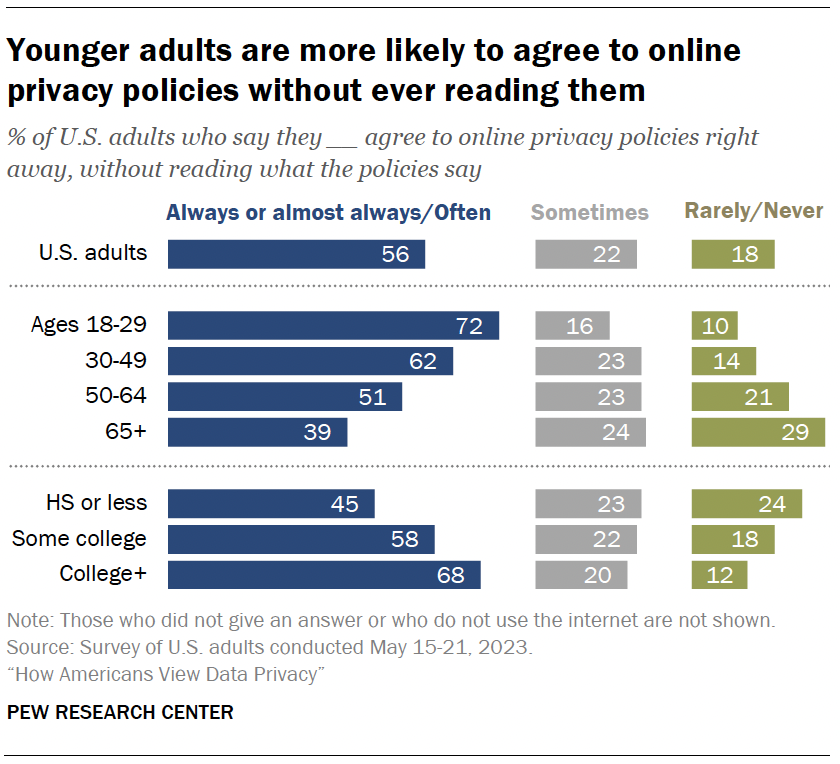

Some 56% of Americans say they always, almost always or often click “agree” right away, without reading what privacy policies say. Another 22% say they do this sometimes. And 18% say they rarely or never agree without reading.

Younger adults are more likely than older adults to say they immediately click “agree” without reading online privacy policies. For example, 72% of adults under 30 say they do this, compared with 39% of those ages 65 and older.

Americans who have more formal education also say they regularly agree to online privacy policies without reading them more often than those with less formal education. Fully 68% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more say they always, almost always or often click “agree” to privacy policies without reading them, compared with 58% of those with some college experience and even smaller shares of those with a high school diploma or less.

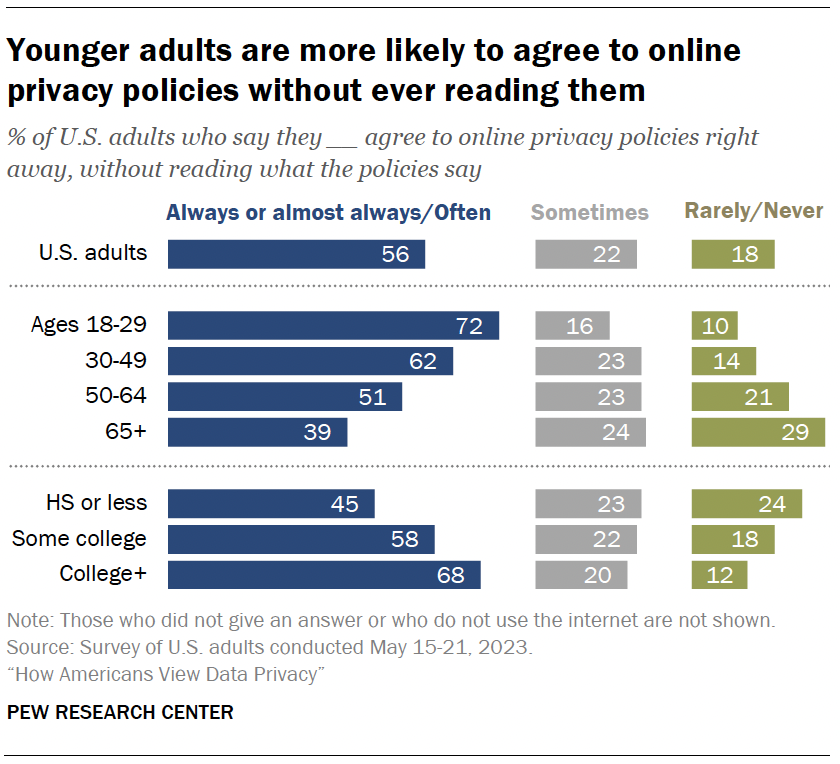

Roughly six-in-ten adults (61%) say privacy policies are not too or not at all effective for communicating how companies are using people’s data. Another 27% say they are somewhat effective for communicating this, and 7% say they are extremely or very effective.

Views about the effectiveness of privacy policies vary widely by formal education level. About three-quarters of those with a bachelor’s degree or more (74%) say that privacy policies are not too or not at all effective for communicating how companies are using people’s data.

That share drops to 63% among those with some college experience and is even lower for those with a high school diploma or less (47%).

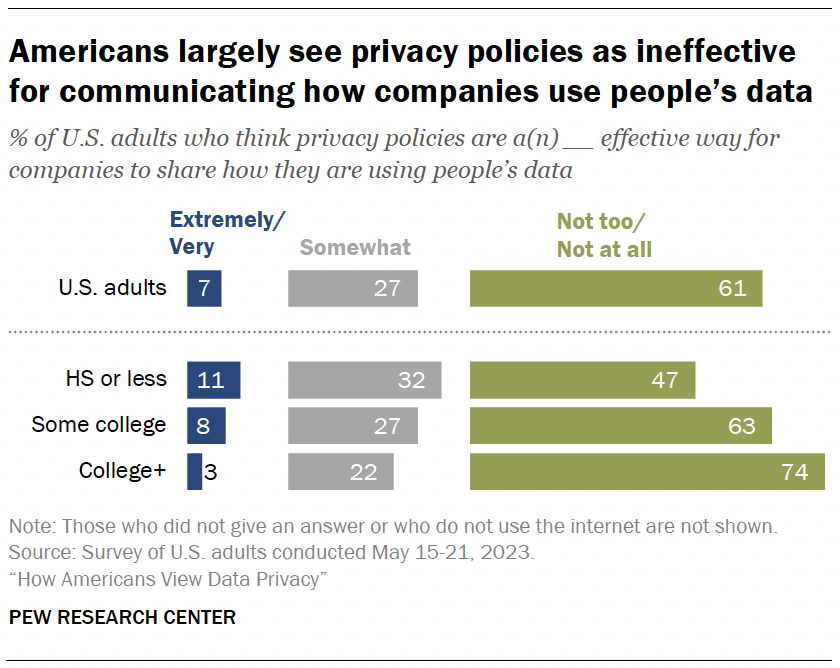

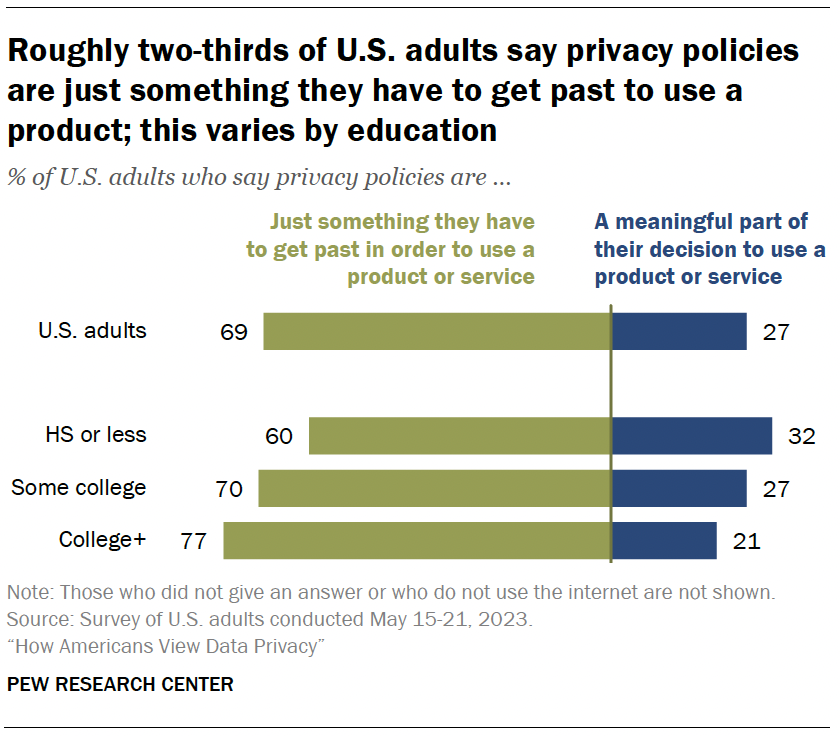

Americans are much more likely to say privacy policies are just something to get past than to consider these policies a meaningful part of their decision to use a product or service (69% vs. 27%).

This varies by level of formal education. Some 77% of adults with a college degree or more say privacy policies are just something they have to get past to use a product or service. This share drops to 70% among those with some college experience and 60% among those with a high school diploma or less.

The survey also explored things people can do to take more control of their online privacy.

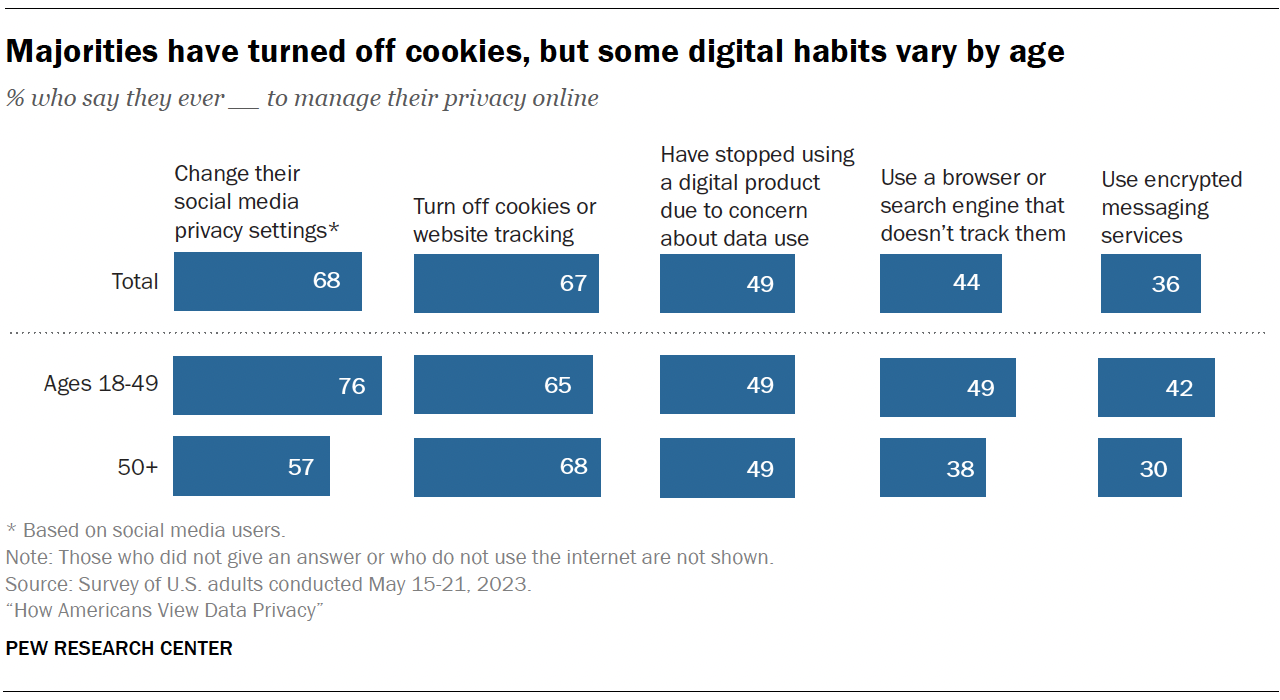

Roughly seven-in-ten social media users (68%) say they have changed their social media privacy settings as a way to manage their online privacy. A similar share of all U.S. adults say they have declined or turned off cookies or other tracking on websites for the same reason.

Smaller shares say they have stopped using a digital device, website or app because they were worried about how their personal information was being used (49%); used a browser or search engine that doesn’t keep track of what they’re doing (44%); or used a messaging app or service that encrypts their private communication with others (36%).

While there are no statistically significant age differences in Americans who have turned off cookies or stopped using a product because of privacy concerns, younger adults stand out on some other privacy-related tactics.

Those with higher levels of formal education are more likely to have done each of the five tasks asked about in this survey.

Roughly three-quarters of adult social media users who have some college experience or more (73%) say they have changed their privacy settings on these sites, compared with 60% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Similarly, Americans who have attended college are more likely than those who have not to say they have turned off website-tracking features (72% vs. 56%).

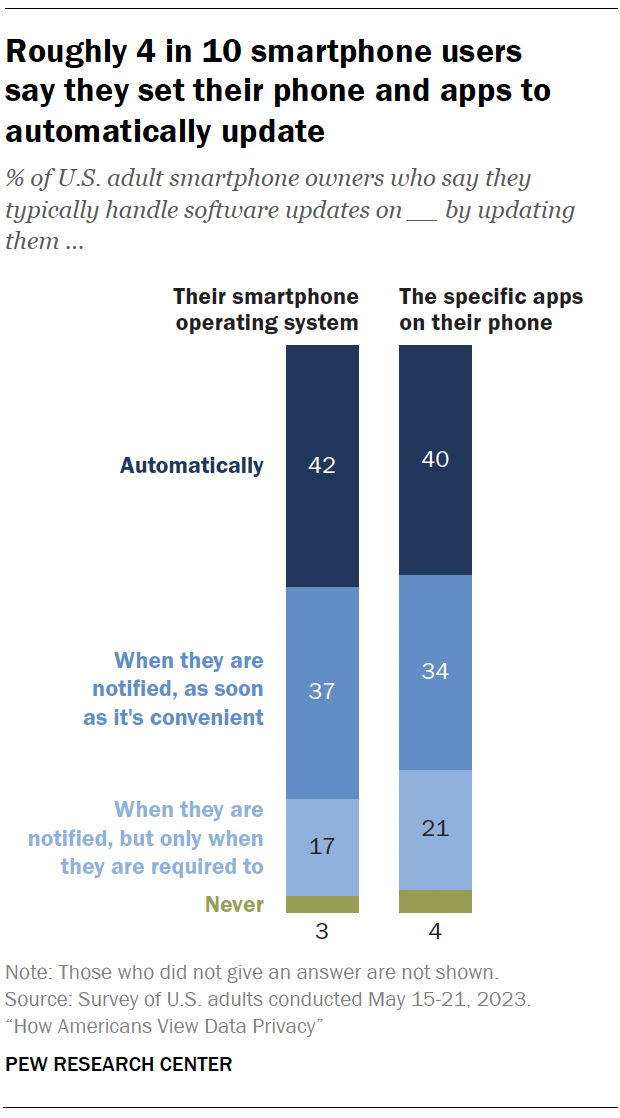

Software updates are an important tool for digital safety and security. They can lower your vulnerability to hackers by updating and correcting security flaws.

Overall, Americans say they update the software on their smartphone and apps, but the urgency in doing so varies.

About four-in-ten smartphone users (42%) say they handle software updates for their smartphone’s operating system by setting them to update automatically.

Another 37% say they do this when they are notified, as soon as it’s convenient for them, while about one-in-five say they update it only when required.

And a much smaller share (3%) say they never update their smartphone operating system.

A similar breakdown is present when asking about how people handle the updates on mobile apps.

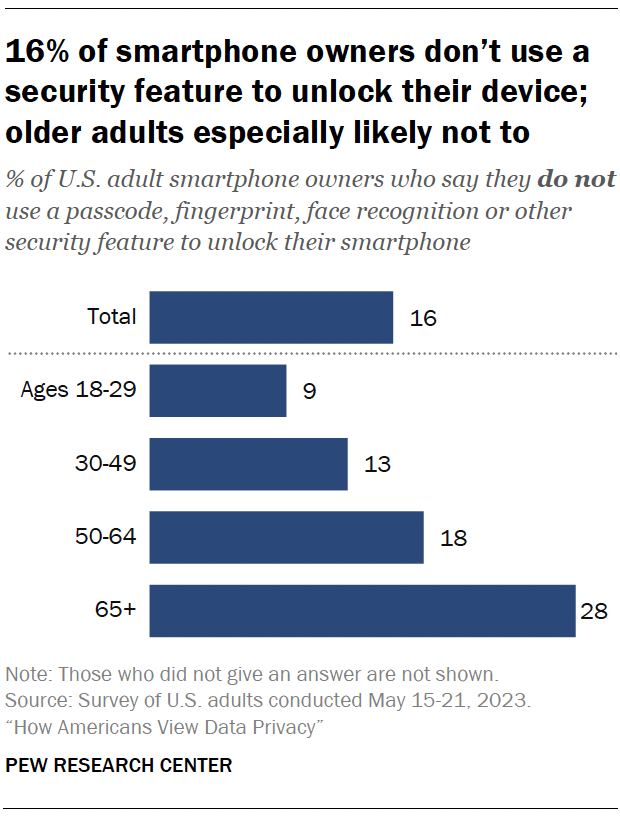

From passwords to fingerprints to face recognition, the way Americans access their smartphones has evolved over the years.

This survey shows most smartphone owners – 83% – say they take steps to safeguard their mobile devices through security features.

But some forgo security features altogether. Among smartphone owners, 16% say they never use a security feature to unlock their phone, such as a passcode, fingerprint or face recognition.

Older users are more likely than younger users to not use the security features on their phones. About three-in-ten of those 65 and older say they don’t use one. This drops to 18% among those 50 to 64 and to 11% for those under 50.

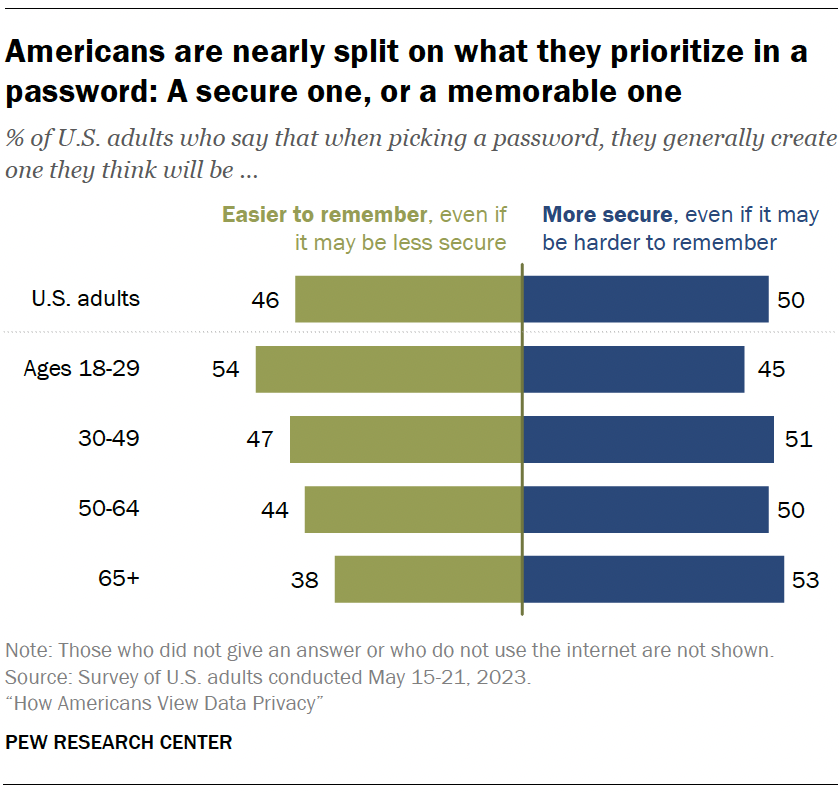

While strong and secure passwords minimize risk, sometimes an easy-to-remember password wins out over strength. Americans are nearly split on how they navigate this trade-off.

Half say they generally create a password that they think will be more secure, even if it may be harder to remember. But a slightly smaller share (46%) opt for one that is easier to remember, even if it may be less secure.

Adults under 30 are more likely than older groups to say they choose a memorable password over a secure one.

Many Americans are stressed about the number of passwords they must keep up with.

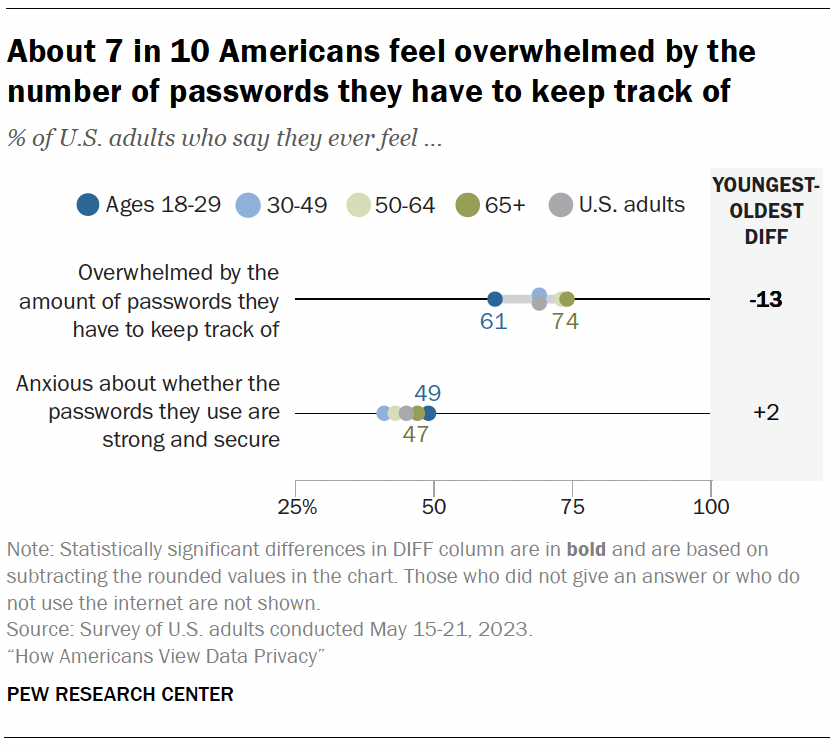

Roughly seven-in-ten (69%) say they feel overwhelmed by the amount of passwords they have to keep track of. At the same time, 45% say they feel anxious about whether their passwords are strong and secure.

Americans ages 30 and older are more likely than younger adults to report feeling overwhelmed by the number of passwords they have to keep track of, although a majority of younger Americans also report feeling this way.

Among adults under 30, 61% say they’ve felt overwhelmed by the amount of passwords they have to keep track of. This compares with 69% of 30- to 49-year-olds and 73% of those 50 and older.

When it comes to feeling anxious about password management:

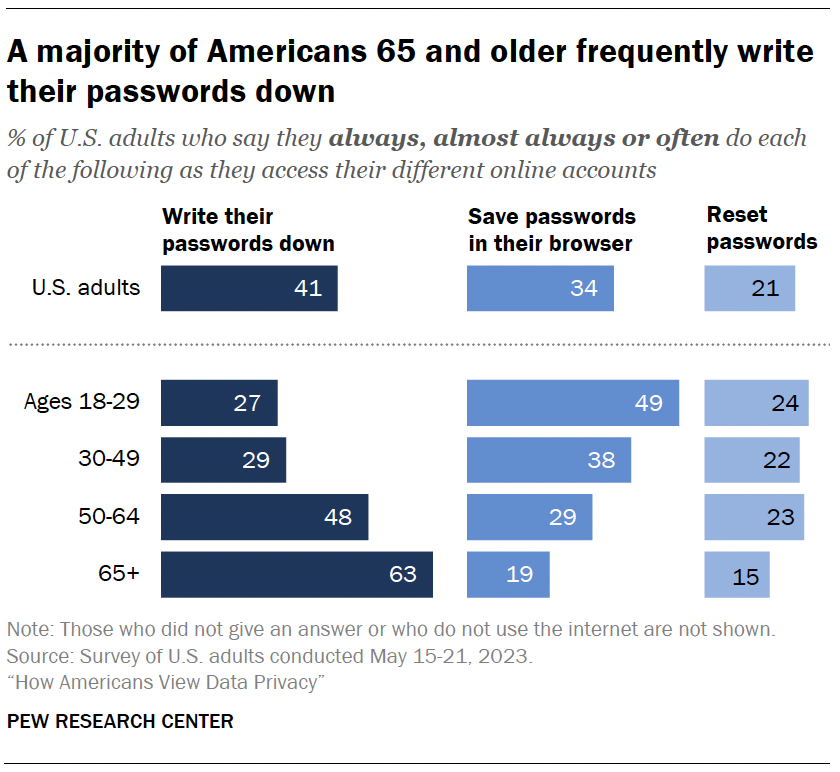

People deal with these kinds of tensions in a variety of ways. The survey asked about three different password management strategies: writing passwords down, saving passwords in their browser and resetting passwords.

Some 41% of Americans say they always, almost always or often write down their passwords. Smaller shares say they save passwords in their browser or reset passwords with this same frequency.

Americans’ experiences with regularly writing down passwords or saving them in a browser vary significantly across age groups.

Some 63% of Americans ages 65 and older say they write their passwords down at least often, compared with 48% of those 50 to 64 and 28% of those under 50.

On the other hand, younger adults lead in regularly saving passwords to their browsers. About half of adults under 30 say they do this regularly, compared with 38% of those ages 30 to 49, 29% of those 50 to 64 and 19% of those 65 and older.

Age differences are more modest for regularly resetting passwords. However, those 65 and older are the least likely to report doing so.

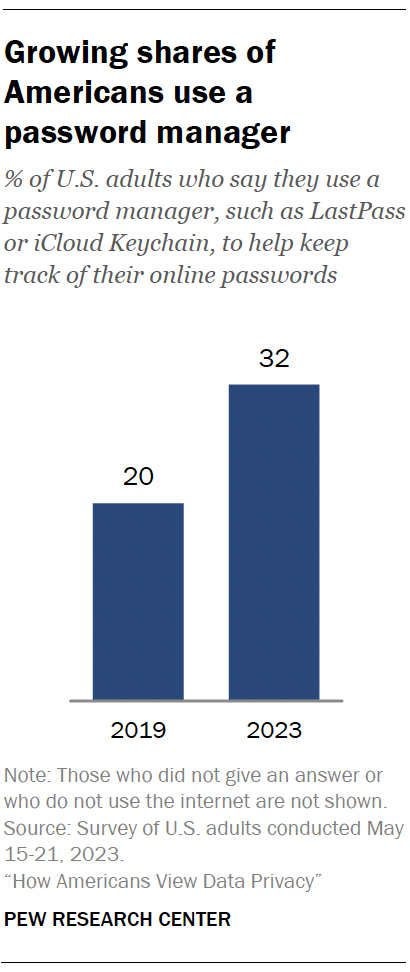

In addition to writing down passwords or saving them in browsers, some are turning to digital tools for help. Growing shares of Americans use digital tools to keep track of their passwords.

The share of Americans who say they use a password manager has risen from 20% in 2019 to 32% today.

About half of those ages 18 to 29 (49%) say they use a password manager. That share drops to 37% among those ages 30 to 49 and to one-quarter or fewer for those 50 and older.

Those with more formal education are more likely than those with less education to say they use password managers.

Roughly four-in-ten of those with a bachelor’s degree or more (38%) say they use one. By comparison, 34% of those with some college experience and 26% with a high school diploma or less say the same.

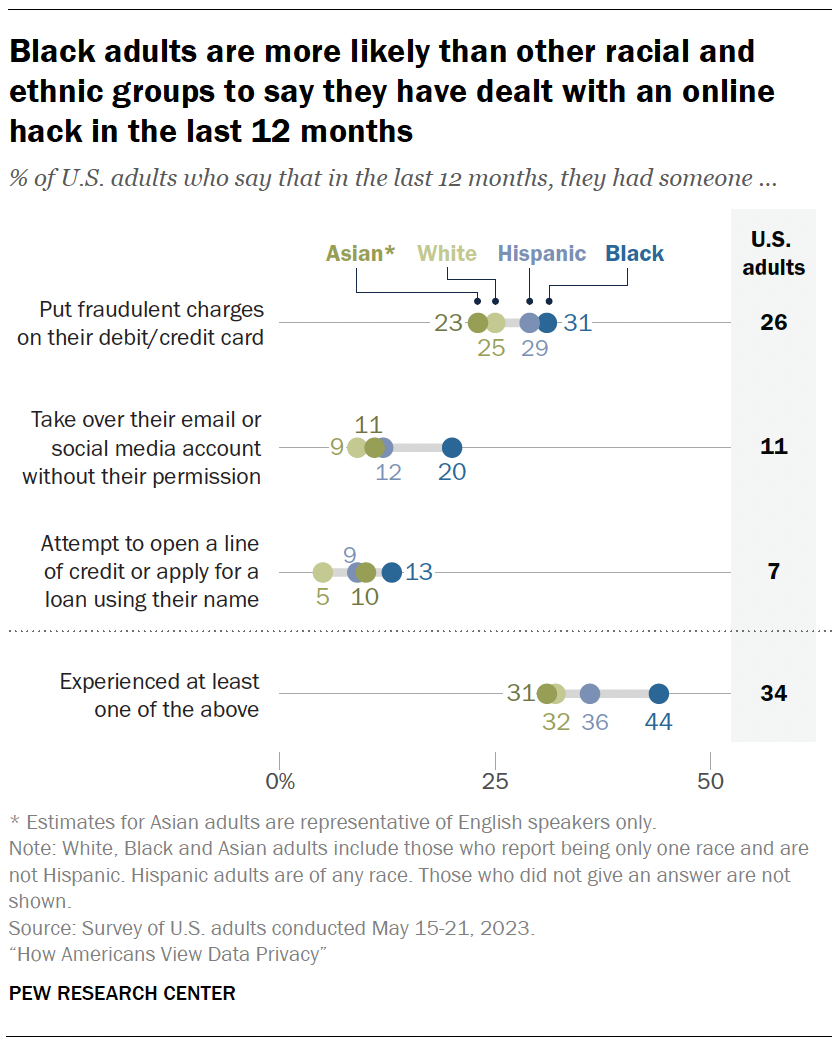

Some Americans – particularly those who are Black – have been the target of hacking.

Roughly a quarter of Americans (26%) say someone put fraudulent charges on their debit or credit card in the last 12 months. Smaller shares say they have had someone take over their email or social media account without their permission (11%) or attempt to open a line of credit or apply for a loan using their name (7%) during this time.

In total, 34% have experienced at least one of these issues in the past year.

Credit card fraud is growing more common. The share who say someone has put fraudulent charges on their debit or credit card rose from 21% in 2019 to 26% today.

Black Americans stand out among other racial and ethnic groups in saying that these types of breaches have happened to them. For example, 20% of Black adults say that in the last 12 months, they had someone take over their email or social media account without their permission. This share drops to about one-in-ten for White, Hispanic or Asian adults.

In total, 44% of Black adults have experienced at least one of these three types of data breaches in the past year. This is higher than their White, Hispanic or Asian counterparts.

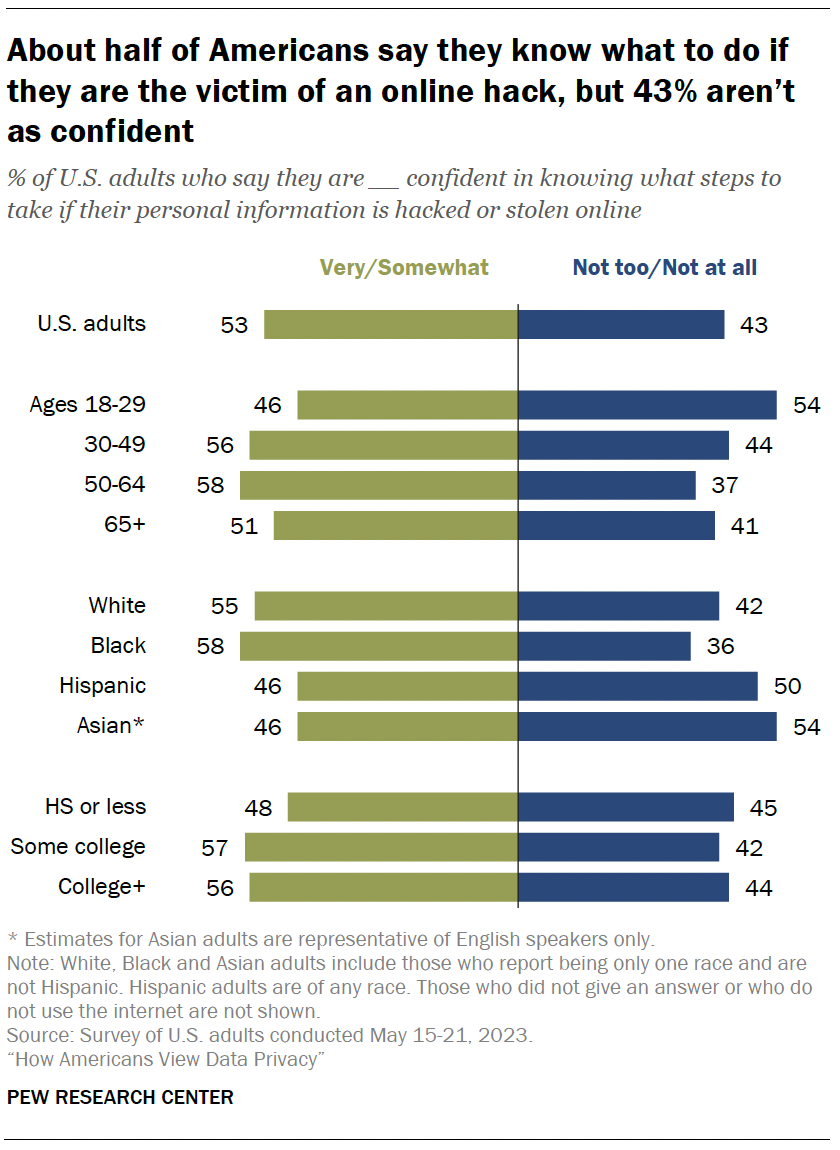

Roughly half of Americans (53%) say they are very or somewhat confident they know what to do if their personal information is hacked or stolen online. But about four-in-ten feel differently, saying they have little to no confidence on what next steps they should take.

Those ages 18 to 29 are less confident than older adults that they know what steps to take if their personal information is stolen online.

Just over half of adults under 30 (54%) say they are not too or not at all confident in knowing what steps to take if their personal information is compromised. Those shares drop to 44% among those ages 30 to 49 and 39% for those 50 and older.

Those with some college experience or more are more likely to say they’re confident in knowing next steps than those with a high school diploma or less (56% vs. 48%).